Will ultrasound-on-a-chip make medical imaging so cheap that anyone can do it?

By Antonio Regalado on November 3, 2014

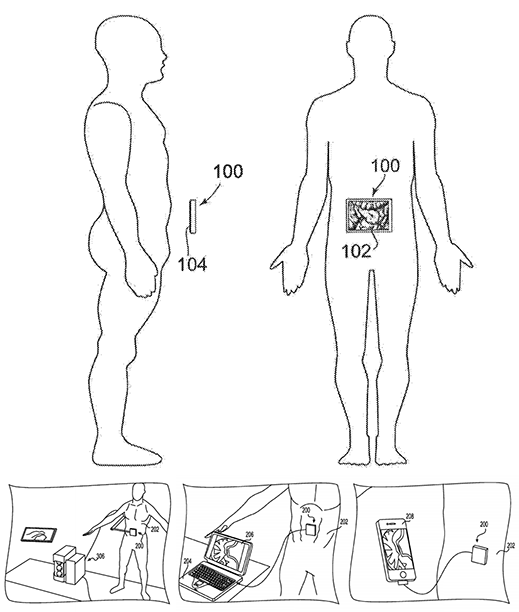

A scanner the size of an iPhone that you could hold up to a person’s chest and see a vivid, moving, 3-D image of what’s inside is being developed by entrepreneur Jonathan Rothberg.

Rothberg says he has raised $100 million to create a medical imaging device that’s nearly “as cheap as a stethoscope” and will “make doctors 100 times as effective.” The technology, which according to patent documents relies on a new kind of ultrasound chip, could eventually lead to new ways to destroy cancer cells with heat, or deliver information to brain cells.

Rothberg has a knack for marrying semiconductor technology to problems in biology. He started and sold two DNA-sequencing companies, 454 and Ion Torrent Systems (see “The $2 Million Genome” and “A Semiconductor DNA Sequencer”), for more than $500 million. The profits have allowed Rothberg, who showed up for an interview wearing worn chinos and a tattered sailor’s belt, to ply the ocean on a 130-foot yacht named Gene Machine and to indulge high-concept hobbies like sequencing the DNA of mathematical geniuses.

The imaging system is being developed by Butterfly Network, a three-year old company that is the furthest advanced of several ventures that Rothberg says will be coming out of 4Combinator, an incubator he has created to start and finance companies that combine medical sensors with a branch of artificial-intelligence science called deep learning.

Rothberg won’t say exactly how Butterfly’s device will work, or what it will look like. “The details will come out when we are on stage selling it. That’s in the next 18 months,” he says. But Rothberg guarantees it will be small, cost a few hundred dollars, connect to a phone, and be able to do things like diagnose breast cancer or visualize a fetus.

Butterfly’s patent applications describe its aim as building compact, versatile new ultrasound scanners that can create 3-D images in real time. Hold it up to a person’s chest, and you would look through “what appears to be a window” into the body, according to the documents.

With the $100 million supplied by Rothberg and investors, which include Stanford University and Germany’s Aeris Capital, Butterfly appears to be placing the largest bet yet by any company on an emerging technology in which ultrasound emitters are etched directly onto a semiconductor wafer, alongside circuits and processors. The devices are known as “capacitive micro-machined ultrasound transducers,” or CMUTs.

Most ultrasound machines use small piezoelectric crystals or ceramics to generate and recieve sound waves. But these have to be carefully wired together, then attached via cables to a separate box to process the signals. Anyone who can integrate ultrasound elements directly onto a computer chip could manufacture them cheaply in large batches, and more easily create the type of arrays needed to produce 3-D images.

“The vision for this product has been around for many years. It remains to be seen whether someone can make it into a market-validated reality.”

Ultrasound is used more often by doctors than any other type of imaging test, including to view a baby during pregnancy, to find tumors in soft tissues like the liver, and more recently to treat prostate cancer by heating up cells with sound waves.

The idea for micromachined ultrasound chips dates to 1994, when Butrus Khuri-Yakub, a Stanford professor who advises Rothberg’s company, built the first one. But none have been a commercial success, despite a decade of interest by companies including General Electric and Philips. This is because they haven’t functioned reliably and have proved difficult to manufacture.

“The vision for this product has been around for many years. It remains to be seen whether someone can make it into a market-validated reality,” says Richard Przybyla, head of circuit design at Chirp Microsystems, a startup in Berkeley, California, that’s developing ultrasound systems that let computers recognize human gestures. “Perhaps what was needed all along is a large investment and a dedicated team.”

Rothberg says he got interested in ultrasound technology because his oldest daughter, now a college student, has tuberous sclerosis. It is a disease that causes seizures and dangerous cysts to grow in the kidneys. In 2011 he underwrote an effort in Cincinnati to test whether high-intensity ultrasound pulses could destroy the kidney tumors by heating them.

What he saw led Rothberg to conclude there was room for improvement. The setup—an MRI machine to see the tumors, and an ultrasound probe to heat them—cost millions of dollars, but wasn’t particularly fast, more like a “laser printer that takes eight days to print and looks like my kids drew it in crayon,” he says. “I set out to make a super-low-cost version of this $6 million machine, to make it 1,000 times cheaper, 1,000 times faster, and a hundred times more precise.”

Rothberg claims there’s a “secret sauce” to Butterfly’s technology, but he won’t reveal it. But it may have as much to do with clever device and circuit design as overcoming the physical limits and manufacturing problems that CMUT technology has faced so far.

One reason to think so is that the company’s cofounder, Nevada Sánchez, previously helped cosmologists design a much cheaper radio telescope with a signal-processing trick called a butterfly network, also the origin of the startup’s name. Also working with the company is Greg Charvat, who joined it from MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, where he developed radar that can see human bodies even through thick stone walls (see “Seeing like Superman”).

During a visit to 4Combinator’s headquarters, which sits inside a marina in Guilford, Connecticut, Charvat and Sanchez showed off a picture of a penny so detailed you could read the letters and numbers on it. They’d taken the image this spring using a prototype chip. “The ultrasound [industry] is basically back in the 1970s. GE and Siemens are building on old concepts,” says Charvat. With chip manufacturing and a few new ideas from radar, he says, “we can image faster, with a wider field of view, and go from millimeter to micrometer resolution.”

Ultrasound works by shooting out sound and then capturing the echo. It can also create beams of focused energy—and chip-based devices could eventually lead to new systems for killing tumor cells. Small devices might also be used as a way to feed information to the brain (it was recently discovered that that neurons can be activated with ultrasonic waves).

“I think it will become better than a human in saying ‘Does this kid have Down syndrome, or a cleft lip?’ And when people are pressed for time it will be superhuman.”

Rothberg says his first goal will be to market an imaging system cheap enough to be used even in the poorest corners of the world. He says the system will depend heavily on software, including techniques developed by artificial intelligence researchers, to comb through banks of images and extract key features that will automate diagnoses.

“We want it to work like ‘panorama’ on an iPhone,” he says, referring to a smartphone function that steers a picture taker to pan across a vista and automatically assembles a composite image. But in addition to recognizing objects—body parts in the case of a fetal exam—and helping the user locate them, Rothberg says the system would also reach preliminary diagnostic conclusions based on pattern-finding software.

“When I have thousands of these images, I think it will become better than a human in saying ‘Does this kid have Down syndrome, or a cleft lip?’ And when people are pressed for time it will be superhuman,” says Rothberg. “I will make a technician able to do this work.”

Rothberg says his incubator has started three other companies in addition to Butterfly, and he’s given each of them between $5 million and $20 million in seed capital. They include a biotechnology firm, Lam Therapeutics, working on treatments connected to tuberous sclerosis; Hyperfine Research, a startup in stealth mode that hasn’t said what type of technology it is developing; and another company that’s unnamed.